Salvador Dalí. “One of the first objections...”

The Scottish Art Review, in the first issue of 1952, published a letter from Salvador Dalí about The Christ in a special issue devoted to the painting, which Glasgow City Council had then just acquired. Given the expectation about this purchase, the editor considered it important to print Dalí’s text, which begins with these words: “One of the first objections...”[1]

“One of the first objections to this painting came from the position of the Christ, that is the position of the Christ, that is, the angle of the vision and the tilting forward of the head. This objection from the religious point of view fails from the fact that my picture was inspired by the drawing made of the Crucifixion by St. John of the Cross himself. In my opinion, it is a drawing made by the saint after an Ecstasy as it is the only drawing ever made by him. This drawing so impressed me the first time I saw it that later in California, in a dream, I saw the Christ in the same position, but in the landscape of Port Lligat, and I heard voices which told me, “Dalí, you must paint this Christ”. The next day I started the painting. Until the very moment I started the composition, I had the intention of putting in all the attributes of the Crucifixion -the nails, the crown of thorns, etc.- and it was my intention to change the blood into red carnations which would have hung from the hands and feet, along with three jasmine flowers issuing from the wound in the side. These flowers would have been executed in the ascetic manner of Zurbaran. But a second dream, just towards the completion of my painting, changed all this, and also perhaps the unconscious influence of a Spanish proverb which says, “A bad Christ, too much blood”. In this second dream I saw again my picture without the anecdotical attributes but just the metaphysical beauty of Christ-God. I also first had the intention of taking as models for the landscape the fishermen of Port Lligat, but in this dream, in place of the fishermen of Port Lligat, there appeared in a boat a figure of a French peasant painted by Le Nain of which the face alone had been changed to resemble a fisherman of Port Lligat. Nevertheless, the fisherman, seen from the back, had a Velasquezian silhouette.

My aesthetic ambition, in this picture, was completely the opposite of all the Christs painted by most of the modern painters, who have all interpreted Him in the expressionistic and contortionistic sense, thus obtaining emotion through ugliness. My principal preoccupation was that my Christ would be beautiful as the God that He is. In artistic texture and technique, I painted the Christ of St. John of the Cross in the manner in which I had already painted my Basket of Bread, which even then, more or less unconsciously, represented the Eucharist for me.

The geometrical construction of the canvas, especially the triangle in which Christ id delineated, was arrived at through the laws of Divine Proporzione by Lucca Paccioli [sic]”[2].

Nuclear Mysticism

During the 1930s, Dalí was one of the greatest exponents of Surrealism, having become involved with the movement in 1929. Freudian theories and the then recent far-reaching discoveries in the physical sciences formed the basis of the new artistic movement, but after the Second World War the attitude towards technological advances of most Surrealists changed radically. Unlike Breton, Dalí extolled the virtues of nuclear physics because they opened the doors to an unknown and mysterious world and to a new dimension between reality and matter.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Dalí and Gala left Europe for the United States, where they lived for eight years before returning to Portlligat in the summer of 1948. This was a time of sweeping change and great uncertainty in which the historic events of the mid-20th century shook the European mentality. As for Dalí, at the end of the 1940s he was engaged in a radical reformulation of his thinking, his interests ranging from Freud and nuclear physics to the Italian Renaissance. In many of his paintings from the 1940s, his ruminations on the structure of the atom and the disintegration and discontinuity of matter are an integral part of his vocabulary. At the same time, he gradually incorporated religious elements, such as the Madonna and Child and the crucifixion of Christ.

However, we should not interpret the painter’s renewed interest in spirituality and mysticism as in any way a reaction against his previous stage. His deep understanding of the Spanish mystical poets (Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross) and the great masters of the Italian Renaissance, together with an intense interest in scientific discoveries, especially in atomic energy and nuclear physics, led him to make the following declaration: “The paroxitic crisis of Dalinian mysticism is based primarily upon the progress of the special sciences of our times, especially upon the quantum physics”[3]. Or again: “I intend to take advantage of the classicism of the Renaissance to give an eternal formula to the new ideas, which can be divided into two groups. Iconography of the subconscious, which is what I have shown the world until today, and painting as a concept of universal cosmogony. Today physics has turned everything on its head and a painter must know this. The painter cannot be a donkey. It was Paccioli [sic] who taught Pierre de la Francesca [sic] all the secrets of physics and geometry”[4].

So began the stage that the artist called “nuclear mysticism” and which he affirmed in the lectures “Why I was sacrilegious, why I am a mystic”(1950)[5] and “Picasso and I” (1951)[6] and in his Mystical Manifesto (1951)[7].

The Mystical Manifesto

The text is accompanied by illustrations in which Dalí brings together his interest in religious subjects and in science and recovers the postulates of quantum mechanics, and especially everything relating to the disintegration of matter. Of particular note are two etchings with a representation of Christ on the cross in the manner of the painting The Christ.

The Manifesto begins with a declaration: “The two most subversive things that can happen to an ex-Surrealist in 1951 are, first, to become a mystic; and second, to know how to draw. These two forms of vigor have just happened to me together and at the same time”. Nuclear physics defines mystical ecstasy, which, for Dalí, is ““super-cheerful”, explosive, disintegrated, supersonic, undulatory and corpuscular, and ultra-gelatinous, for it is the aesthetic blooming of the maximum of paradisiacal happiness that a human being can have on earth”[8].

This text is a complete statement of principles. The artist justifies the appearance of religious themes in his work, the use of the golden ratio and his turning towards the Italian Renaissance, prompted by his desire to become a classic-a classic with a will to transcendence who uses scientific terms such as wave-corpuscle duality or the integration or disintegration of matter, and incorporates them into his new artistic discourse.

Dalí also expresses his desire to become a classic and a “saviour” of modern painting,[9] a mystic who will, from now on, concern himself with religious themes, and this is why he declares that his new kingdom is the soul and that he sees in religion and the love of God the only hope for humanity. Dalí’s engagement with one of the key themes of Christianity-the crucifixion of Christ, the saviour of humanity-was inspired by John of the Cross, as the consummation of a moment of transformation and culmination of this longing. In his conviction that religion and physics were the vital issues (at that time), he declared that he paints “in constant explosion. In nuclear bombing from the scientific point of view it is possible to approach the real mystery of life”[10], and thus brought his Surrealist period to an end.

Dalí and His Models

Any consideration of the models and references, in matters of technique and style, that led Salvador Dalí to paint The Christ, will inevitably look to Spanish painters such as Alonso Cano, Francisco de Goya, Francisco de Zurbarán and, above all, Diego Velázquez. Velázquez, the greatest exponent of Spanish Baroque painting, was a constant in the work of the Surrealist artist. Dalí himself tells us that, as a child, “when night fell, I could not cross my parents’ bedroom because of the portrait of this dead brother and the reproduction of Christ by Velázquez which hung there”[11]. It is very likely that Dalí subsequently contemplated the Velázquez painting at length on his visits to the Museo del Prado, during his four years as a student in Madrid.

Following on from the example afforded by Velázquez, Dalí set out to create a work that would be totally different from those of his contemporaries, giving us a dignified, serene Christ, whose face and wounds are not shown, and present him from a unique perspective.

The figure of Christ depicted by several of the painters mentioned above and in most representations in the history of art has one constant: that of a Christ whose suffering is shown; a Christ whose face and crown of thorns and the nails in his hands and feet are shown. The purpose of such a depiction is to move us as viewers.

“It is because I went through cubism and surrealism without forsaking classicism that my Christ does not resemble other Christs-at the same time I believe that it is the least expressionist of all those that have been painted in modern times but the newest-it is a Christ as beautiful as the God that he is”[12].

To embody his idea, the artist looked for a model that would represent the pinnacle of Apollonian beauty. Thanks to his friendship and professional relationship with Jack Warner, head of the famous Warner Brothers film studios, Dalí came into contact with the man who was to be the model for Christ: the Californian gymnast and action film stuntman Russ Saunders, who had worked on such major productions as The Three Musketeers (1948) and Singing in the Rain (1952).

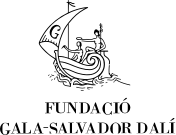

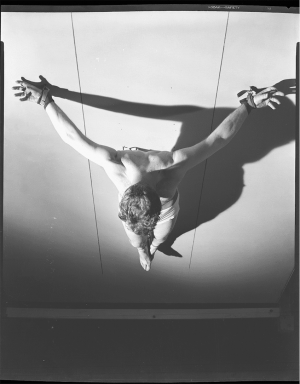

We know that, in addition to drawing from life, the painter often used photographs, which provided him with a tool for the execution of his works. Thanks to a set of unpublished negatives with the stamp of Weiman & Lester, conserved in the archives of the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, we know how the painter and his model worked together to give form to the artist’s idea. These negatives also make it clear that another model was involved in addition to Saunders.

-

Salvador Dalí, “A letter from Salvador Dalí”, The Scottish Art Review, vol. IV, no. 1, 1952, Glasgow, p. 5.

-

Ibid

-

“Use Dictionary to Figure Dali’s Theory”, Capital Journal, 20/06/1951, Salem.

-

Translated from “Salvador Dalí”, El Correo Catalán, 05/12/1948, Barcelona.

-

Lecture given by Salvador Dalí in the Ateneu Barcelonès on 30 October 1950.

-

Lecture given by Salvador Dalí in the Teatro María Guerrero, Madrid on 11 November 1951.

-

Salvador Dalí, Manifeste mystique, Robert J. Godet, Paris, 1951.

-

Salvador Dalí, Mystical Manifesto (1951). In Salvador Dalí, The Collected Writings of Salvador Dalí, The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg (Florida), 2017, p. 363. Edited and translated by Haim Finkelstein.

-

The given name Salvador means “saviour”.

-

“Surrealism Ended, Says Artist Dalí”, Post, 03/12/1951, Houston.

-

Salvador Dalí, Louis Pauwels, The Passions according to Dalí, The Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg (Florida), 1985, p. 52.

-

Salvador Dalí, “Picasso and I” (1951). In A. Reynolds Morse, Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí: a preliminary study in their similarities and contrasts, The Salvador Dalí Museum, Cleveland (Ohio), 1973, p. 54.