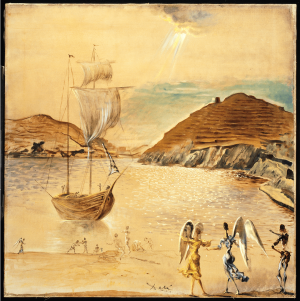

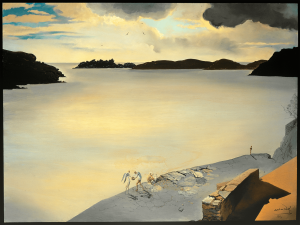

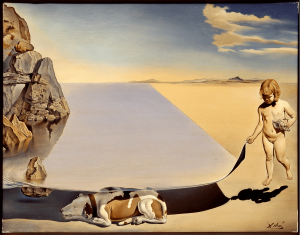

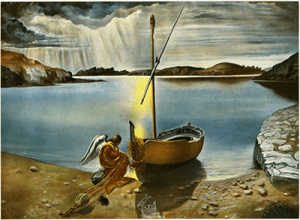

The bay of Portlligat

The bay of Portlligat

“This drawing [by John of the Cross] so impressed me the first time I saw it that later in California, in a dream, I saw the Christ in the same position, but in the landscape of Portlligat”[1].

Portlligat and, by extension, Cap de Creus, are places that the artist had known well since his childhood, and it was not for nothing that this was where the painter chose, together with Gala, to establish his only permanent residence, in which he had his studio. But above all Portlligat and its environs are where Dalí’s imaginary roamed, the places that we find depicted in the great majority of his works from every period.

Still today the rugged landscape of Portlligat conveys a certain poetry, a certain melancholy. This is a space in which a great calm prevails, yet at the same time it exudes an air of tension, and these are chief among the sensations we experience as we contemplate The Christ, thanks to the position of the son of God in contrast to the landscape spread out below him. As if Christ, in the sorrow of his sacrifice, had need of the silence, solitude and seclusion of this closed-in port.

For Dalí, Portlligat, its landscape, was what configured his world-a world which, during the years of exile in the United States, he painted from memory and which, after an absence of eight years, he needed to encounter again. This was a physical, organic need beyond aesthetic pleasure. Portlligat and the surrounding landscape were part of him as a person; more than that, they constitute one of the elements that forged the personality and emotions of the artist. Portlligat is the affective landscape that Dalí painted time and again. It is one of the constants in his work, one of the factors that have enabled it to become universal: “I need the localism of Portlligat just as Raphael needed the landscape of Urbino, to arrive at the universal by the path of what is particular”[2]. This is evidenced by the numerous works in which Portlligat is the setting we all recognise, just as the real landscape of Cap de Creus reminds us of the artist’s work.

And of note among the works in which the bay of Portlligat is clearly identifiable are those from the same creative period as The Christ.

The fishermen

As his models, Dalí very often used people and objects that were very close to him, in the broadest sense of the term, physically and emotionally, and we can identify, in some of his works, local characters from Cadaqués, many of them fishermen. In the case of The Christ, the landscape is completed with a commonplace scene in the bay of fishermen working on the shore. However, for this canvas, Dalí imagined figures with a very specific origin: “I had also been tempted at first to take as a model, for the background, the fishermen of Portlligat, but in this dream, in the place of the fishermen of Portlligat there appeared, in a boat, the figure of a French peasant painted by Le Nain, of which only the face had changed to resemble a Portlligat fisherman. However, the fisherman, seen from the back, had a silhouette in the style of Velázquez”[3].