The Christ in Glasgow

In 1951, Dalí exhibited his painting The Christ at the Lefevre gallery in London. The following year, the city of Glasgow purchased it for its museum. The driving force behind the acquisition was the director of that institution, Tom Honeyman, who intuited the importance of the painting within the artist’s body of work. In addition to its undeniable beauty and brilliant execution, it links two key aspects of the painter’s mature period: his ambition to become a classic and his transition towards nuclear mysticism.

A controversial acquisition

The Glasgow Museums’ purchase of The Christ was not without controversy. Salvador Dalí sold the painting and the reproduction rights to it to the city of Glasgow for quite a considerable sum at the time, sparking a heated polemic. Especially in Scottish academic circles, it was argued that the money should be used instead to create exhibition spaces for local artists. Nevertheless, Dalí’s The Christ was exhibited for the first time in Glasgow in June 1952 in what quickly became a genuine ‘art event’ in the city. On 23 April 1961, a visitor to the museum tried to destroy the painting, throwing a stone at it that ripped the canvas. As a result, it had to be taken down and restored.

In 1993, the painting was temporarily moved to Glasgow’s St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art, where it would remain until 2006, when it was permanently installed at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. In 2023, The Christ returned to the land where it was painted for the first time since 1952, for a temporary exhibition at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres.

The moment of creation

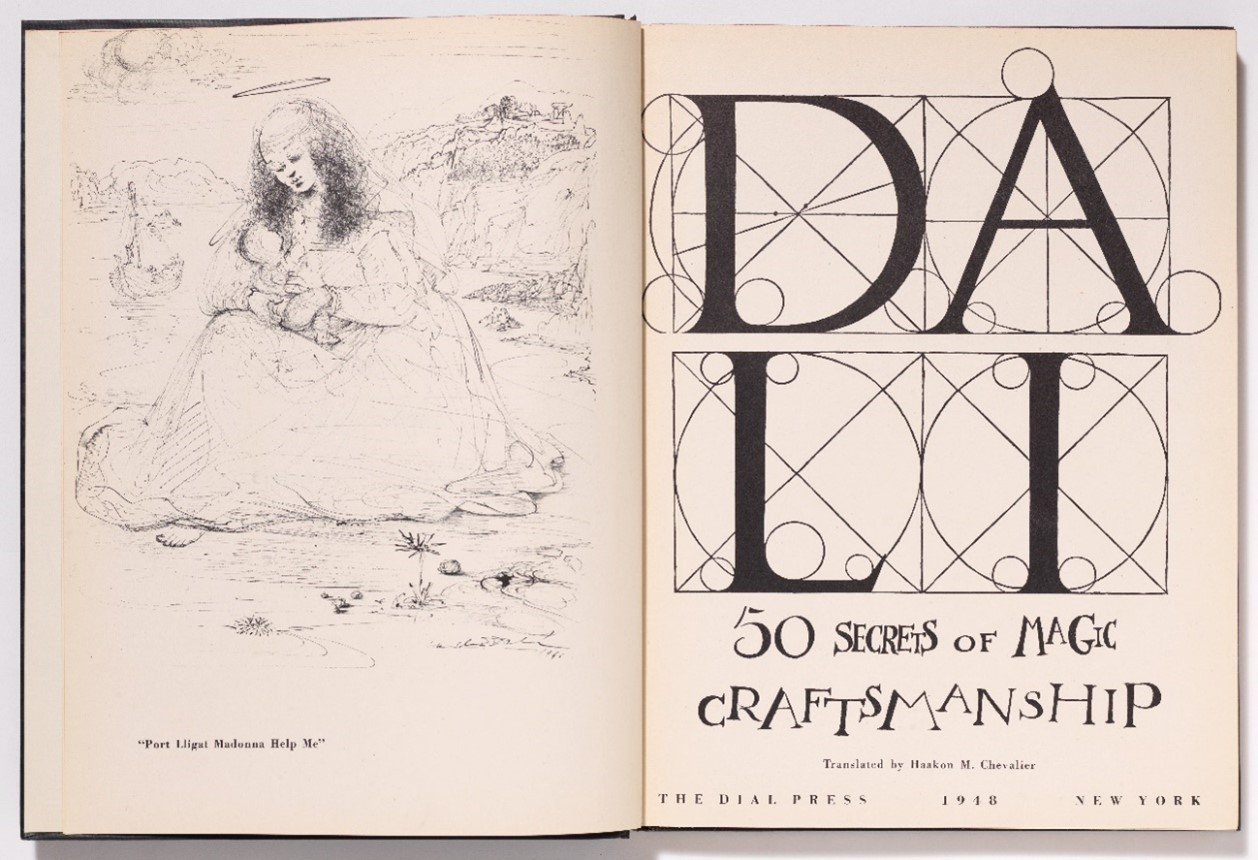

Dalí’s The Christ exemplifies the thinking that defined this period of maturity and transition for the artist. At the same time, it embodies the ideas that Dalí put forward in his treatise on painting 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, published in 1948. In that book, he broke down, step by step, the ‘recipes’ that young painters should follow to create a masterpiece, explaining his work method, the ideal set-up for a studio, and the materials needed to put it all into action.

A Christ as beautiful as the God that He is

The Scottish Art Review published a letter from Dalí about this painting in its first issue of 1952. In it, he wrote: ‘My aesthetic ambition in this picture was completely the opposite of all the Christs painted by most of the modern painters, who have all interpreted Him in the expressionistic and contortionistic sense, thus obtaining emotion through ugliness. My principal preoccupation was that my Christ would be beautiful as the God that He is.’

By the late 1940s, Dalí had begun to reformulate his thinking. In addition to atomic structure and the disintegration and discontinuity of matter, he became interested in mysticism and religious themes, such as the crucifixion or the Virgin Mary. He embarked on a period that he called ‘nuclear mysticism’, in which, unlike his fellow surrealists, he did not lose interest in the breakthroughs in the physical sciences from the turn of the 20th century. He also continued to advocate following a Renaissance approach, enhanced by his deep knowledge of Spanish mystical poets, such as St John of the Cross and St Teresa of Ávila.

The creative process

Dalí painted a Christ in an unusual pose, a Christ of great beauty, without the suffering described in the Scriptures. As he himself explained, the mission to paint this work, as well as the details of its execution, were revealed to him in two dreams, recalling the tradition of revelations seen in mystical processes.

Drawing as the foundation

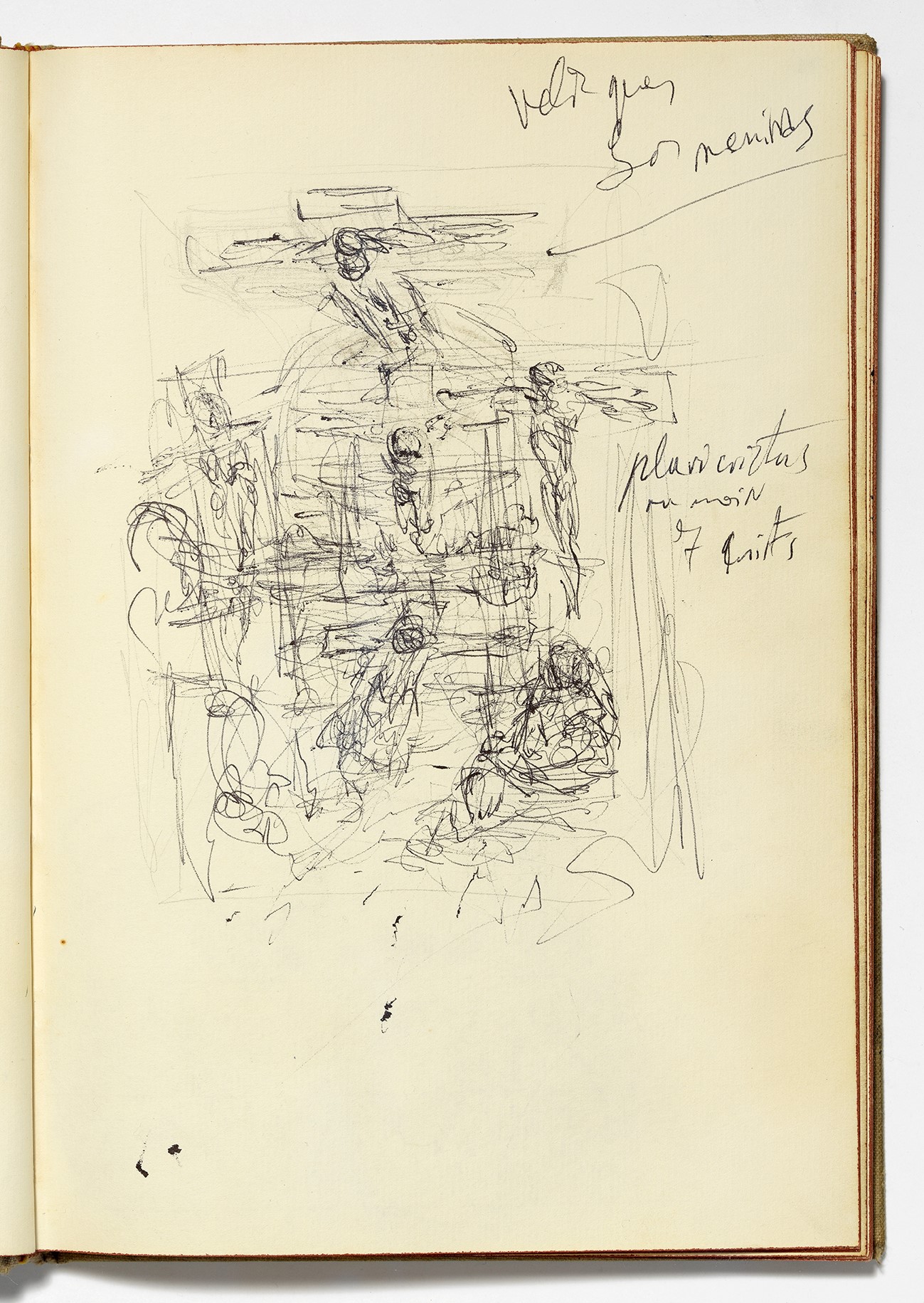

Dalí began the creation of this painting with a series of drawings that illustrate his creative process and how he transferred the idea of painting a Christ as ‘beautiful as the God that He is’ to the canvas. Among them are several compositions reminiscent of the figure of Christ sketched by St John of the Cross for a reliquary currently preserved in Ávila. The great majority, however, show a free-floating foreshortened figure viewed from the front, albeit with variations, such as the image of the reflected Christ.

To materialize his idea, Dalí then sought out an ideal model to convey the pinnacle of Apollonian beauty his Christ would embody. Through his professional relationship and friendship with Jack Warner, head of the Warner Bros. film studio, he was introduced to the California-based gymnast and action film stuntman Russ Saunders. As a stunt double, Saunders had participated in films such as The Three Musketeers (1948) or Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In addition to the sketches he did with the live model, unpublished negatives conserved in the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation’s archives offer additional insight into his work process and show that he also worked from photographs of him. Finally, he transferred his creation to the canvas in accordance with the tradition mapped out in 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship.

The iconography of The Christ

Dalí depicted the passion of Christ from a highly unusual perspective, clearly inspired by the Spanish mystics, especially St John of the Cross, and with a very elaborate geometry: Christ is shown suspended over the bay of Portlligat, Dalí’s vital landscape, which has been rendered in a twilit tone with blues that the photographer Juan Gyenes once remarked he ‘had never seen anywhere else’.

The Christ of Portlligat

In the letter published in The Scottish Art Review in 1952, Dalí explained that he initially intended to include all the attributes of the Crucifixion in The Christ. He had also planned to transform the blood into red carnations and depict three jasmine flowers sprouting from the wound on his side. However, a second revelation, or dream, caused him to change his mind, leading him to paint ‘just the metaphysical beauty of Christ-God’.

Christ hovers over Portlligat Bay in such a way as to convey an overwhelming sense of unity with it. Portlligat is Dalí’s affective landscape. It is a constant in his work, something he painted time and again, and one of the elements that allowed him to use the ultra-local to become universal. This landscape is rounded out with an everyday scene on the Portlligat waterfront: fishermen at work on the shore. But these figures have a very specific origin. In Dalí’s own words, ‘In a boat, [there appeared] the figure of a French peasant painted by Le Nain, of which only the face had changed to resemble a Portlligat fisherman. However, the fisherman, seen from the back, had a silhouette in the style of Velázquez.’