The Dalinian Triangle is the geometric shape that would appear on a map of Catalonia if you were to draw a line connecting the towns of Púbol, Portlligat and Figueres. These three towns help explain the life and career of an artist who, having achieved international acclaim, nevertheless remained deeply rooted in his homeland. Spanning an area of nearly 40 square kilometres, this space contains the main elements that help to understand Salvador Dalí’s universe: the landscape, light, architecture, geology, customs, legends, food, etc. In short, everything to be found around the house-museums in Portlligat and Púbol and the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres.

Both a tangible concept and a land rendered mythical by Dalí, the Dalinian Triangle allows us to explore the artist’s universe, serving as a gateway to a world that offers visitors a wealth of unique sensations and experiences.

In this privileged place, reality and the sublime almost touch. My mystical paradise begins in the plains of the Empordà, is surrounded by the hills of the Albera range, and reaches its fullness in the bay of Cadaqués. This land is my eternal inspiration.

Salvador Dalí

A Journey into the Surrealist World of Salvador Dalí

The Dalinian Triangle is a fascinating route that connects three iconic sites in the Empordà region of Catalonia, each intrinsically linked to the life and work of the renowned surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. This journey offers a deep immersion into the artist’s creative and personal universe.

‘Where, if not in my own town, should the most extravagant and solid of my work endure? Where, if not here?’

Salvador Dalí

By the early 1960s, Salvador Dalí had already achieved considerable international acclaim as an artist and had exhibited his work all over the world. That was when the municipal authorities of Figueres, the city where he was born in 1904, proposed creating a monographic room dedicated to the artist in the future Empordà Museum. The artist’s response was clear: he would create his own museum in the city of his birth.

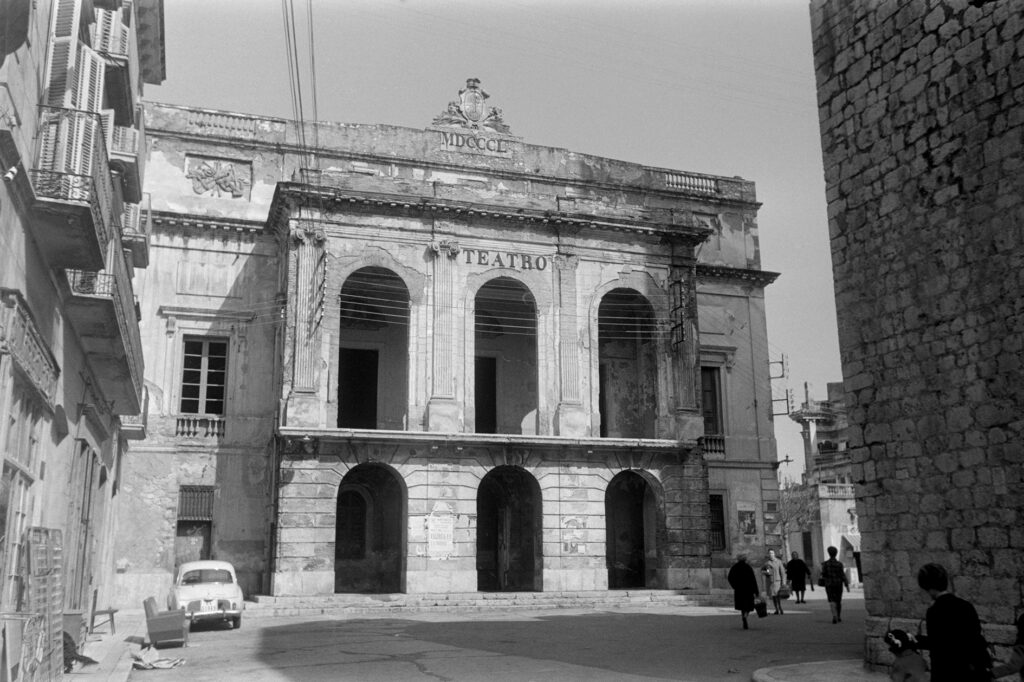

No doubt inspired by the theatrical element, as well as his predilection for places in ruins – he was particularly fond of the Palazzo Reale in Milan, damaged by air raids in World War II – Dalí set his sights on the old municipal theatre built by the architect Josep Roca i Bros in 1850. It was, at once, a testimony to neoclassical civil architecture and a rare example of an Italian-style theatre. Partially destroyed by a fire at the end of the Spanish Civil War that left only its peripheral structure intact, the building was chosen by the artist as the site of his great surrealist monument. But other, more personal factors were also at play, which help shed additional light on Dali’s choice. It is the theatre in the town where he was born; it is located next to the Church of Sant Pere (St Peter), where he was baptized; and it is the former home of the Societat de Concerts (Concert Society), where he first exhibited his work, in 1919.

In 1961, Dalí announced the museum’s creation to the press. Two years later, the Spanish Directorate General for Fine Arts commissioned the building’s renovation from the architect Joaquim Ros de Ramis, with the collaboration of the municipal architect Alexandre Bonaterra. Although some work was done in the 1960s, the lion’s share was carried out between 1970 and 1974. Throughout that period, Dalí remained wholly dedicated to the museum project, both conceptually and executively, designing and creating the various areas down to the most minor detail. He turned each part of the old municipal theatre into a new museum gallery through an artistic intervention aimed at preserving its surviving aura and architecture. In addition to the works that Dalí would end up placing in the museum, the architectural and decorative interventions he proposed for the courtyard, stage and some of the three-storey structure’s corridors are both among his most outstanding contributions and a compendium of universal references to the history of art.

In 1970, Dalí presented the museum project at the Musée Gustave Moreau in Paris. This time, he also offered a glimpse of the first works to be displayed at the museum: the backdrop for the ballet Labyrinth, which he would instal on the stage, and the main panel to decorate the ceiling of the Palace of the Wind room, which he had already begun to paint in his studio at Portlligat. The year 1972 saw the installation of one of the most emblematic elements: the transparent dome-shaped lattice structure that crowns the stage. Dalí had been struck by the innovative geodesic structures of the American architect Buckminster Fuller, although it was the Spanish architect Emilio Pérez Piñero, based out of Calasparra, who ultimately built the dome, which has since become a symbol of both the museum and the city of Figueres itself.

Notwithstanding a pre-inauguration event held in 1973 on the occasion of the exhibition of the Dalí-designed jewellery then owned by the Owen Cheatham Foundation, the Dalí Theatre-Museum was officially inaugurated on 28 September 1974. But Dalí never stopped working on it and continued his efforts until his death. The following month, work began on the installation of the Rainy Taxi, which now presides over the former theatre stalls, welcoming visitors to the museum. In 1975, Dalí and Antoni Pitxot teamed up to create the ‘grotesque monsters’ for the courtyard’s central windows, an extremely complex set of sculptures made from branches, old gargoyles from the Church of Sant Pere, snails and stones from Cap de Creus. That same year, the Monument to Francesc Pujols was installed outside the museum, in front of the main façade. This tribute by Dalí to the Catalan writer and philosopher, father of hyparxiology, should be understood in the context of their mutual friendship and deep admiration.

The old theatre that Dalí had transformed was later enlarged with the addition of the new rooms in the Galatea Tower, formerly, the Gorgot Tower, an adjacent building acquired by the Dalí Theatre-Museum Board of Trustees in 1981. The artist designed the decoration of the exterior façade, which consists of the iconic pans de tres crostons (a traditional three-cornered type of bread) and the eggs and mannequins that crown the upper cornice. This area initially housed numerous works from the artist’s bequest, the stereoscopic works, the anamorphoses, and the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation’s new acquisitions. Today, it is also a temporary exhibition hall. In 2001, the museum was again enlarged with the inauguration of the Dalí-Jewels section, adjacent to the Galatea Tower. Here visitors can see the thirty-seven pieces of jewellery made of gold and precious gemstones from the old Owen Cheatham Collection that Dalí designed, as well as his preparatory drawings for them.

Nowhere better exemplifies what a total artist Dalí was than this museum. By his wish, visitors have the opportunity to learn about his career as an artist through a broad selection of works both from a chronological perspective and in terms of the variety of types of works and techniques he used in his creative process. This collection is also the most extensive and representative of all the arts in which Dalí expressed himself, including paintings, sculptures, objects, jewellery, drawings, graphic work, installations (most of them done ex professo, specifically for this space), stereoscopic works, holograms, etc. It moreover includes some of his most notable literary creations, such as The Tragic Myth of Millet’s Angelus or his Ten Recipes for Immortality.

Most of these works were created or selected by Dalí expressly for this museum. Only the new acquisitions made by the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation since 1991 have been added. The artist rounded out the selection of his own work with references or tributes to his most revered artistic predecessors, especially Raphael, Vermeer and Velázquez, whom he both identified with and transcended. As a result, this museum also pays homage to the great historical masters who inspired him. Furthermore, alongside his own work, the artist also included works by several of his contemporaries, from friends such as Evarist Vallès and Antoni Pitxot to international artists such as Marcel Duchamp, John de Andrea, Ernst Fuchs or Wolf Vostell. The third-floor Masterpiece Room is also home to works from his private collection by historic and established artists such as El Greco, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Gerard Dou, Marià Fortuny or Modest Urgell.

‘I want my museum to be like a single block, a maze, a great surrealist object. It will be an absolutely theatrical museum. The people who come to see it will leave feeling they have had a theatrical dream.’ Probably for this same reason, there is no set order for visiting the rooms of the Dalí Theatre-Museum. Dalí expected visitors to play an active role and, thus, to be able to tour the premises on their own, engaging in their own readings and endowing every work of art with meaning. It is a unique and immersive experience, a trip through the mind of Dalí that offers insight into his work, his enigmas and his importance in the universal history of art.

Every room or area is an entity or space in itself: the Courtyard, the Stage, the Treasure Room, the Fishmonger’s Hall, or the Palace of the Wind allow viewers to journey from Dalí’s first artistic experiences and formative periods in the 1920s to some of the masterpieces from his surrealist period and nuclear mysticism, with its emphasis on his passion for science and new technologies, to his paintings from the 1980s, which would be the artist’s final creations.

Some of the most outstanding works include Self-Portrait with “L’Humanité” (1923), Port Alguer (1924), The Spectre of Sex-Appeal (1932), Buste de femme rétrospectif (Retrospective Bust of a Woman) (1933), Portrait de Gala portant deux côtelettes en équilibre sur son épaule (Portrait of Gala with Two Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder) (1933), Soft Self-Portrait with Grilled Bacon (1941), Poetry of America – The Cosmic Athletes (1943), Galarina (1944–45), The Basket of Bread (1945), Atomic Leda (1949) and Galatea of the Spheres (1952) or Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936/1964).

‘You cannot understand my painting without knowing Portlligat’

Salvador Dalí

Portlligat Bay opens up along the road from Cadaqués to Cap de Creus. The artist knew this setting well: growing up, he and his family had relocated from Figueres each summer to their holiday home on the beach of Es Llaner. Cadaqués is also where Dalí had one of his first studios, on the top floor of a fisherman’s cottage. The artist regularly spent his summers in these places until he fell out with his father, in 1929, over his relationship with Gala and was forced to look for a new place to settle down with her.

On 20 August 1930, Dalí bought a small fisherman’s hut from Lídia Nogués, nicknamed ‘la Ben Plantada’ (the Beautiful), with an advance from the Viscount of Noailles for the painting La vieillesse de Guillaume Tell (The Old Age of William Tell). This first hut was a small, austere place measuring some 22 square metres and lacking all amenities: it did not even have electricity. ‘It was there that I learned to impoverish myself, to limit and hone my thinking until it acquired an axe-like effectiveness, where blood tasted like blood and honey like honey. A hard life, without metaphor or wine, a life with the light of eternity’, Dalí would later recall.

A multipurpose room was planned for the ground floor, which would serve as a dining room, bedroom, studio and hall, whilst the upper floor was set aside for a bathroom and a kitchen. In September 1930, Dalí purchased a second hut, which he would reform in 1932 together with a small annex that today is the house-museum’s lobby area. In 1935, the contractor Emili Puignau took on the project of enlarging the home, resulting in two new structures: the first studio (today, the Yellow Room) and the bedroom (or Birds’ Room). However, in the wake of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Dalí and Gala left Portlligat, and, in 1940, took up permanent residence in the United States, where they remained until 1948. As a result, the house in Portlligat remained uninhabited for several years, until, in 1944, the painter Josep Maria Prim moved in with his family.

When Dalí and Gala returned from the United States in 1948, they undertook another final enlargement of the house. To this end, they acquired the Ca l’Arsenio hut, which was transformed into the library and living room, and the Olive Grove plot. The following year, they purchased three more huts, which became the bedroom, the kitchen, and some rooms for the help. That year also saw the start of the work for the artist’s first-floor studio. Completed in the spring of 1950, the room is accessed through a doorway shaped like a truncated isosceles triangle, expressly designed by Dalí. The open-plan interior is a bright white space, bathed in the light that streams in through the two rectangular windows, one directly overlooking Portlligat Bay and the Sa Farnera island, the other offering views of the slopes to the north. This was his creative sanctuary, steeped in the light and landscape of Cap de Creus, the setting that is essential to understand his creative output. Here, Dalí painted some of his most important works, using an easel and a mechanical stretcher that allowed him to hold and adjust the height of large canvases. On that device, he would paint La Batalla de Tetuán (Homenaje a Mariano Fortuny) (The Battle of Tetuan (Homage to Marià Fortuny)) and The Apotheosis of the Dollar around 1965, as well as the panels for the ceiling of the Palace of the Wind room in the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres around 1972.

Dalí’s workspace was eventually enlarged with the Models’ Room and an attic, where he also worked from time to time. The Pigeon Loft, located in the Olive Grove, where the artist is known to have created some of his sculptures, was built around 1954.

Dalí also occasionally worked en plein air, in different outdoor places around the house. He would set up on the balcony, in the Olive Grove or at the edge of the property near the ‘Milky Way’, a white limestone path created in 1958 that runs parallel to the sea. The courtyard and its surrounding walls, built to make this spot an inaccessible enclosure, were added around 1960. The painter’s lifelong attraction for the natural environment and organic forms of Cap de Creus is thus clear. The surviving images of Dalí at work in these outdoor settings show how the artist merged with his immediate surroundings in a way that conditioned the very foundations of his creations.

The 1960s and 1970s saw additional reforms. The Oval Room, an almost hemispherical space inspired by a design Dalí had done in 1957 for an Acapulco nightclub, was completed in the summer of 1961. The Summer Dining Room was built in 1963, and, in 1969, work began on the plans for a pool, which was finished in the summer of 1971, although Dalí continued to work on it after, tweaking different details.

The result of all these reforms and enlargements is a sprawling labyrinthine structure that twists and turns in a series of spaces linked by narrow corridors, subtle level changes and blind passageways. The windows in each room – of myriad shapes and sizes – pursue a common goal: to frame the natural landscape, making Portlligat Bay, the constant point of reference in Dalí’s work, accessible from inside every room as well. These spaces, packed with countless objects and mementos belonging to Dalí, are decorated with features that make them particularly cosy: carpets, limestone, dried flowers, velvet upholstery, antique furniture, and so on. Gala saw to the décor, purchasing a variety of furniture from antique dealers in Olot and La Bisbal.

In addition to his home and creative space, Portlligat also became the site of some very peculiar social activity, especially for Dalí. Often, it was even used as a photography studio or set for television productions, where photographers, journalists, media types and other interested people from all over had the opportunity to discover the artist and the persona, two inextricably linked dimensions of Dalí’s artistic and creative process by his own intention. Gala often accompanied him on these occasions, although she kept a lower profile, as she was less inclined to make public appearances or statements. In fact, beginning in the early 1970s, Gala largely withdrew to her own space, in the castle in Púbol, which Dalí offered her as a gift and symbol of courtly love.

This social activity in Portlligat reached its apogee between 1972 and 1974. In a sense, public life in Portlligat became a venue for meeting and creating with other contemporary artists, perhaps emulating, more or less directly, Andy Warhol’s Factory in the United States.

Since 4 August 2009, visitors have also been able to explore another space located in the Olive Grove area, a circular construction that the artist used as an additional studio, especially to make sculptures and for performances. The glass skylights allowed Dalí to paint feet, such as the ones on view in the Palace of the Wind (the former first-floor reception hall of the Theatre-Museum in Figueres). The artist encrusted perforated earthenware vessels onto the turret’s exterior to whistle when the tramontana wind blew. Inside is a piano that Dalí used in various artistic performances, as well as two projectors simultaneously showing different audiovisual clips of the artist: feature stories from the 1960s and 1970s about Dalí and the house in Portlligat.

‘I had to give Gala a setting more solemnly worthy of our love. That is why I gave her a mansion built on the remains of a twelfth-century castle, in La Bisbal, the old Púbol castle, for her to reign as the absolute sovereign – to the point that I go there only when invited in her own hand. It was enough that I decorated the ceilings so that whenever she looks up she finds me in her heaven.’

Salvador Dalí

From the outset, both Gala and Salvador Dalí were captivated by the mysterious and romantic aspect of the architectural complex, which they found in a state of ruin. Together, they re-imagined the interior and exterior spaces and gave instructions for their restoration to their friend, the master builder Emilio Puignau. At Gala’s behest, the artist personally saw to the decoration, designing some elements and painting false architectural details on the walls and ceilings. The entire castle is a celebration of the cult of Gala, the undisputed protagonist of this part of the Dalinian Triangle, which has a personality all its own.

In 1969, Dalí purchased the architectural complex known as Púbol Castle, thereby fulfilling a promise made to Gala in the 1930s. Gala was delighted by the mediaeval building, in particular by the garden and flowers, especially the roses, which reminded her of the garden in Crimea where she had spent several summer holidays as a child. The property, however, was utterly dilapidated, its ceilings sagging and collapsed, the walls rent with cracks, and the garden largely gone wild. All of this lent it a romantic air that the Dalís endeavoured to preserve in the process of restoring it.

With the technical assistance of Emilio Puignau, Gala and Dalí chose to shore up the building’s structure without trying to conceal the scars left by the passage of time, which were a source of fascination for the couple. Puignau himself recalled Dalí’s enthusiastic account in this regard: ‘I have seen something sublime in the façade: not only is it cracked, but it forms a projection in the crack that gives the impression of there having been a cataclysm, an earthquake, with one part holding fast whilst the other split off and collapsed. So that must not be touched; it must be left as it is.’

Gala was equally enthusiastic and keenly interested in following the work on the castle. In a letter to Puignau, she described what she saw as their responsibility: ‘As you will have realized, Púbol is my “workhorse”, or, rather, ours. I am fascinated by the potential of this house in ruins, which could also give rise to a monster. So far, working together, we have always succeeded in Portlligat. That little house has become famous; you see it reproduced everywhere, even today. So we have a great responsibility, you and I, for a new and great success.’ Her involvement in the Púbol project was absolute; she supervised and managed the entire restoration process and was the driving force behind the interior decoration, for which she commissioned a series of projects from Dalí, who, thanks to his artistic versatility, provided a new reading of the interior spaces.

Many drawings preserved in the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation’s collections bear witness to the creative process behind the various areas and features created expressly for the castle, such as the designs for the fireplaces or the skylight table. At Gala’s request, the artist also conceived of: ‘1. A fifteen-metre ceiling depicting a nocturnal hole in the Mediterranean sky from which surreal objects are falling. 2. Chairs that do not touch the ground. 3. Six stork-legged elephant fountains leading to the pool with the twenty-seven ceramic busts of Richard Wagner. 4. Screens to disguise the radiators painted with radiators using the optical illusion technique. 5. Solid gold taps and shower fixtures for the bathroom.’

As for the interior, the result is a closed, mysterious, private and sober place, with areas of great beauty, such as the old kitchen converted into a bathroom, the scenographic Shields Room or the majestic Piano Room. For the castle’s exterior, the old French-style garden was Italianized and enhanced with Dalinian interventions. Among the most striking are the elephant fountains, which seem to be advancing towards the castle, and the fountain with classicalizing airs featuring a spout in the shape of a monkfish head, reminiscent of the famous monsters in the Garden of Bomarzo in Rome that Dalí so admired. Other features, such as the gazebo or the benches with fleur-de-lis backrests, further heighten the romantic atmosphere of this place so well suited, as Gala once said, ‘for having a sentimental tête-à-tête’.

Following her death, in 1982, what had been Gala’s most cherished space in the final years of her life became her eternal resting place: she is buried in the crypt, located in what was once the old castle’s tithe room. Determined not to be separated from her, Dalí took up residence at Púbol. There, he would recover from her loss and establish what would be his final studio. In those years, Gala’s blue room became his bedroom, and the home’s attic was used to store the works that Dalí had left in New York and Paris. But in 1984, the artist had to be hospitalized after being badly burned in an accidental fire, and he never returned to Púbol.

In 1996, the castle in Púbol was opened to the public. The complex includes a temporary exhibition hall that mainly explores the figure of Gala and her fashion collection, which includes pieces by internationally renowned designers and of great heritage value.