The visit

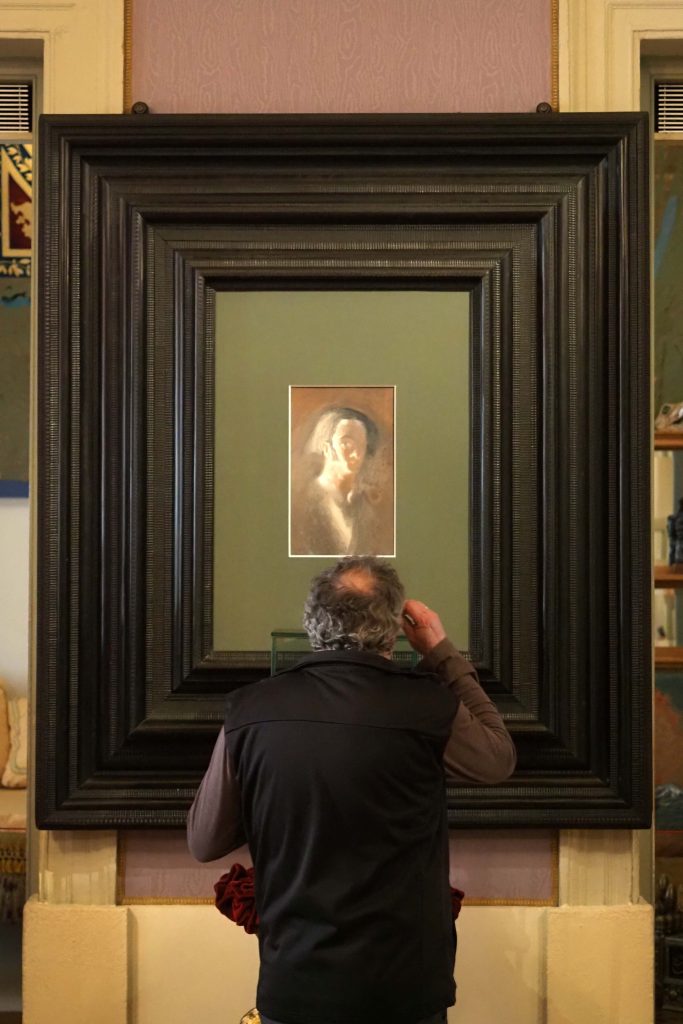

Immerse yourself in Salvador Dalí’s last great work, the museum built on the ruins of the former Figueres Municipal Theatre, conceived of and designed by the artist himself. A unique opportunity to observe, experience and enjoy the work and thought of Salvador Dalí.

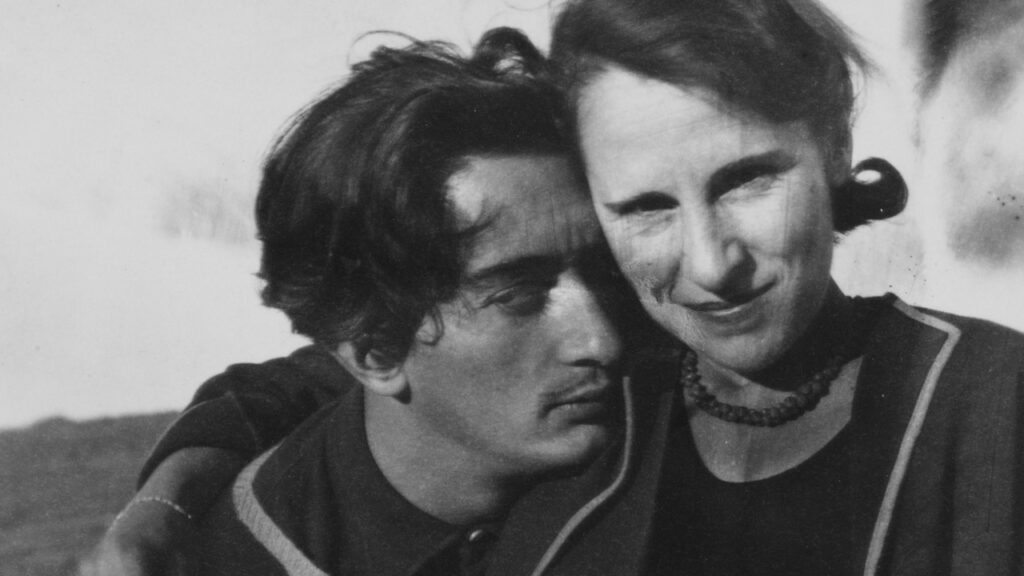

Inaugurated in 1974, the Dalí Theatre-Museum is home to the world’s most extensive collection of the artist’s work, offering the ideal setting to learn about his career, from his earliest creative experiences and iconic surrealist creations to the works of the last years of his life.

Check the opening hours

Opening Hours

1 January – 31 March: Tuesday–Sunday |10:30 a.m.–6:00 p.m.*

1 April – 31 May: Tuesday–Sunday,|9:30 a.m.–6:00 p.m.*

1 June – 30 June: Tuesday–Sunday,10:30 a.m.–6:00 p.m.*

1 July – 31 August: Everyday | 9:00 a.m–8:00 p.m

1 September – 30 September: Tuesday–Sunday | 9:30 a.m | 6:00 p.m

1 October – 31 December: Tuesday–Sunday, 10:30 a.m.–6:00 p.m.*

Access to the museum and the ticket office is allowed until 45 minutes before closing time.

The rooms close 15 minutes before the established time.

*Exceptionally open: 6 January, 14 and 21 April, 9 and 23 June, 1 and 8 September, 10 November and 8 and 29 December.

* Exceptionally closed: 1 January and 25 December. On December 24th the Dalí Theatre-Museum closes at 3:00 p.m.

Gala i Salvador Dalí Square, 5, 17600 Figueres, Girona.

How to get there

General admission 18 / 29’5 €. Reduced admission 15 / 25,5 €

Prices

- Reservations recommended

General admission: 18,00 € (Online); 20,00 € (Ticket desk).

Reduced admission: 15,00 € (Online); 17,00 € (Ticket desk). Students 18+ (proof required), juniors (ages 9 to 17), Carnet Jove holders, pensioners 65+, degree of disability of 33% and one companion with a disability (proof required)

o Degree of disability of 50% (and one companion): Free.

Children (ages 0 to 8): Free.

ICOM members (ICOM membership card required). Free.Guided visits: 26,00 € (general); 23,00 € (reduced).

o Groups (25 people or more): 14,00 € (Online); 16,00 € (Ticket desk).

1 July– 31 August

General: 21,50 € (Online); 23,50 € (Ticket desk).

Reduced: 17,50 € (Online); 19,50 € (Ticket desk).

Guided visits: 29,50 € (general); 25,50 € (reduced).

Map of Dalí Theatre-Museum

Download

Given the Dalí Theatre-Museum’s complexity, we recommend checking the visit map.

About the Dalí Theatre-Museum

More information

The Dalí Theatre-Museum

The Dalí Theatre-Museum, the world’s largest surrealist object, is located in the former Figueres Municipal Theatre.

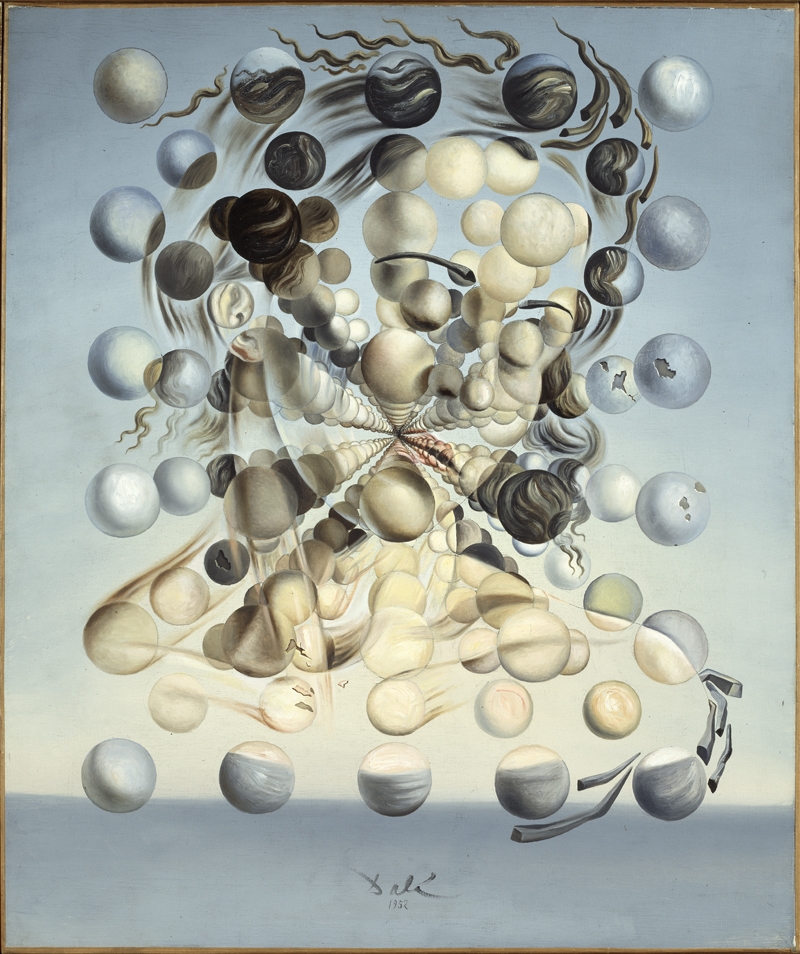

At the Dalí Theatre-Museum, you can see the largest collection of the artist’s work, consisting of more than 1,500 pieces encompassing all manner of styles and formats (paintings, drawings, sculptures, prints, stereoscopic works, installations, holograms, photographs, etc.), as well as works by other artists whom Salvador Dalí admired.

There are also new areas added in the last years of Dalí’s life and after his death, such as the Crypt, Galatea Tower or Dalí-Jewels rooms.

Route and visitable areas

The Dalí Theatre-Museum consists of two museum areas.

The first is the former theatre, destroyed in a fire and converted into the Theatre-Museum according to Salvador Dalí’s own criteria and design (Rooms 1 to 18). Together, these rooms make up a single art object, in which each part is inextricably linked to the rest.

The second consists of a set of rooms resulting from the successive extensions of the Dalí Theatre-Museum, including the temporary exhibition rooms (rooms 19 to 22) and the collection of jewelry designed by Salvador Dalí (rooms 23 and 24).

Are you visiting the museum in a wheelchair or do you have reduced mobility? Check the accessibility conditions here.

Admission Policy

Buy your ticket online. Remember to download the confirmation document, as you will need to show the reservation code at the ticket desk or entrance.

Exchanges and refunds are not provided for reasons beyond the museum’s control.

Flash photography and photography requiring other special equipment are prohibited.

Smoking, eating and drinking inside the building and littering in the courtyards, gardens or street are prohibited.

No type of guided tour may be given without prior authorization from the museum.

All visitors must show and hold on to their ticket, as well as, in the case of reduced or free admission, the corresponding proof of eligibility.

Minors under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult.

Purses, rucksacks, etc., will be inspected by security at the entrance. For security reasons, any potentially dangerous items (knives, etc.) will be retained and must be retrieved at the end of the visit.

Entry with any type of object larger than 35 x 35 x 25 cm, luggage or bulky items in general, rucksacks or other bags worn on the back, pushchairs, or any other item that the authorized staff consider a security risk for the museum is prohibited.

Bulky items, living beings, jewellery, money or valuables, dangerous items or items posing a public safety or health risk may not be checked at the left-luggage office.

The museum cannot under any circumstances be responsible for checked items.

Pets are not allowed (except for guide dogs).

Clothing must be respectful of all sensibilities. In particular, visitors wearing clothing and/or accessories that might pose an obstacle in the event of an emergency evacuation will be denied admission.

Posters, banners or any sort of protest performance inside the building are prohibited and will be grounds for immediate ejection.

Visitors must follow the instructions of the museum staff at all times.

Services and accessibility

There is a left-luggage service located in the museum lobby for checking items. Checked items may be retrieved at the left-luggage office located in the shop and exit area.

The gift shop is located by the museum exit.

The toilets are on the ground-floor, below the stage. The museum has accessible toilets for visitors with reduced mobility and baby changing facilities.

The entrance for visitors with reduced mobility is located in Plaça Gala-Dalí, next to Wolf Vostell’s sculpture ‘Obelisk Television’. Please notify the museum’s admission staff in advance.

For more information, see the Accessibility page

Specific rules for groups and private guide services

No type of guided tour may be given without prior authorization from the museum.

Guides, professionals and companions seeking to provide guide services inside the museum must request prior authorization in the Dalí Theatre-Museum lobby.

Under no circumstances may explanations be provided to groups of more than 25 people, except in the Courtyard (Room 2) and Dome (Room 3) areas.

School groups including minors making self-guided visits of the museum will have to split up and the minor students will have to be accompanied by a responsible teacher at all times.

The room staff have the authority to enforce these rules.

Filming and Photography Policy

Non-flash photography and photography not involving the use of tripods or professional equipment are allowed. In other cases, the museum staff may retain the camera until the owner completes the visit. Public dissemination of images taken inside the Dalí Museums is subject to licensing and payment of royalties.

Request permission to film or take photographs

Groups with accessibility needs

Would you like to visit the Dalí Theatre-Museum with a group with special needs?

The Dalí Museums are part of the Apropa Cultura network.

If you’re not yet a member, register your organisation and enjoy numerous benefits.

Regala Dalí

Would you like to give a unique experience as a gift? With Regala Dalí, you can purchase an open-date ticket for the Dalí Museums, perfect for gifting with complete flexibility. When making the purchase, no visit date or time is assigned. You will receive a redeemable code, which the recipient can later use to obtain the final ticket by selecting an available date and time slot.