As with his paintings and sculptures, the artist’s graphic work has been documented from the beginning to the end of his career. His exceptional talent in this field is clear in the works from the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation’s collection, many of which are exhibited at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres. These creations reflect the variety of processes and techniques used in the production of the artist’s graphic work, as a result of his close collaborations with master printers and publishers.

Salvador Dalí’s graphic work stands out for the wealth of materials, techniques, procedures and formats that it brings together. Monotypes, intaglio prints, lithographs, serigraphs, stencils and photomechanical reproductions are some of the processes he used most often in his work. This allowed him to create many different types of works, from individual prints, to artist’s books, bookplates and other limited editions. All of this bears witness to Dalí’s commitment to the technical advances of his time and the reproducibility of the image.

His first documented creations, from 1924, include the etching Tête de jeune fille (Head of a Young Girl) and the drypoint Retrato de mi padre (Portrait of My Father), intimist pieces made in a family setting.However, it was not until the early 1930s that his contribution to the field of graphic arts became apparent. This apex coincided with Dalí’s move to Paris, the centre of the art world, and his joining of the surrealists.

His graphic work from the 1930s includes landmark creations in which Dalí made use of intaglio techniques, mainly for different limited-edition books. He began with an initial frontispiece for André Breton’s Second Manifesto of Surrealism and continued with prints for Breton and Paul Éluard’sL’Immaculée Conception (The Immaculate Conception) and the French poet René Char’s Artine. The artist’s book La Femme Visible (The Visible Woman), entirely conceived by Dalí, also dates from this period. All these prints, made in 1930, stand out for their bold spirit. These early works caught the eye of the great Swiss publisher Albert Skira, who retained Dalí to create 34 illustrations for his edition of Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) by Isidore Ducasse, better known by his nom de plume Comte de Lautréaumont, which was published in 1934. This work served as a beacon for the surrealist group, who saw a kindred spirit in the young Uruguayan author. Today, Dalí’s prints from the 1930s are considered some of the most outstanding works of the surrealist period.

For much of the 1940s, when Dalí and Gala moved to the United States, fleeing from the Second World War, the artist did not produce any editions of graphic work. Instead, he cultivated his skills as an illustrator, providing artwork for some of the great classics of universal literature for American publishers. These were generally popular editions intended for the general public, such as The Life and Achievements of the Renowned Don Quixote de la Mancha, The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini from 1946 orthe Essays of Michel de Montaigne from 1947. It was not until that same year that the artist was commissioned by the Print Club of Cleveland to make the print St. George and the Dragon. This same period also saw the production of Leda Atomica, a monochromatic engraving with the same composition, only in reverse, as the two paintings of the same name created around 1947.

In the early 1950s, after returning to Europe and establishing his residence and main workshop in Portlligat, Dalí was commissioned by the Italian government to do the illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy, which were ultimately reproduced by the French publisher Joseph Forêt in 1959. In 1957, he teamed up with the same publisher on a first edition of Pages Choisies de Don Quichotte de la Manche, consisting of an original, colourful series of lithographs that stand out for the expressiveness and action of the line work. Two years later, he was commissioned to illustrate the brochure and postcards for the Tour de France, which would be reproduced using photogravure.

Thereafter, throughout the 1960s, his output increased thanks to projects done in different media and techniques, mainly in Paris and New York. The great diversity of subjects is a direct reflection of the plurality of the commissions. These included, among others, the illustration of many highly acclaimed literary works, such as Horace Walpole’s famous Gothic novel Le Chateau d’Otrante, from 1764, which was re-released two hundred years later in an edition featuring ten of Dalí’s engravings; the Poèmes Secrets that Guillaume Apollinaire wrote to his fiancée Madeleine during the First World War, which Dalí illustrated in 1967 with a total of 18 etchings and drypoint prints; the 1969 edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland published in New York, with included 12 full-colour reproductions and an etching on the cover; and the one hundred illustrations he did for the Biblia Sacra in 1969, a luxury Latin-language edition of the Bible.

From 1970 until the early 1980s, Dalí once again significantly increased his production of series of graphic works. He began to do both book commissions and an enormous variety of single prints, completing the work in France, Spain and the United States. However, it is in the illustration of artist’s books from this last period, related to the ancient world, ancient literature, esotericism and alchemy, that Dalí offered an exceptional demonstration of his commitment to this discipline. At this point, his rapport with master craftsmen, a very broad guild of professionals from the world of printing and books with whom he had maintained close ties from his beginnings as an artist, was clear.

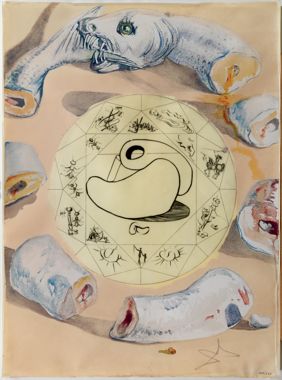

All three of his great works from the 1970s, which took the form of book-objects, are prominently displayed at the Dalí Theatre-Museum. Dix Recettes d’Immortalité (Ten Recipes for Immortality), a text written by Dalí containing his reflections on life and death, was published in 1973, together with eleven prints made with various intaglio techniques. In Moïse et le Monothéisme (Moses and Monotheism) from 1974, the artist engages in a dialogue with Sigmund Freud through the text that the great Austrian psychoanalyst wrote on the origins of monotheism just before his death in 1939. The last of these book-objects, Alchimie des Philosophes (Alchemy of the Philosophers), is a luxury edition for bibliophiles that includes ancient alchemical texts dating from the 3rd to the 17th centuries, from various renowned libraries, which together offer a universal vision of knowledge and mysticism from different world cultures. Its contents range from Taoist texts from the Ming dynasty to some of the most representative texts of Western mediaeval alchemy, reproduced in facsimile and illustrated by Dalí with full-colour mixed media prints on parchment. The book’s cover design moreover features ‘Llullian wheels’, a reference to the Ars Magna, a machine created as a ‘logical-mathematical’ device by the mediaeval philosopher Ramon Llull.

The graphic work reflects the broad vision of the arts that Dalí maintained over a career spanning more than fifty uninterrupted years. And whilst his prints are highly heterogeneous – due, in part, to his commitment to an endless array of multiple and simultaneous projects in different countries – it is clear that the commissions that fascinated the artist became works that fascinated his audience too. His contributions, whether in the form of single prints, series of prints, artist’s books or book-objects, enriched the world of graphic art and enhance our appreciation of Salvador Dalí.