- Dalí and the Great Tradition: the importance of the trips to Italy

- Dalí, Renaissance artist

- Dalí-Raphael, a prolonged revery

Lucia Moni – Centre for Dalinian Studies, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí

Dalí and the Great Tradition: the importance of the trips to Italy

“Begin by drawing and painting like the old masters. After that do as you see fit - you will always be respected."[1]

Salvador Dalí decided that the catalogue of his first solo exhibition, at the Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona, in November 1925, should end with a quote from Élie Faure: 'A great painter has the right to take up the tradition only once he has passed through revolution, which is the search for his own reality."[2] The words of the French art historian and essayist evidently had a special resonance for Dalí. In his pursuit of a language of his own the young painter, in his early twenties, was experimenting with the most diverse styles (Impressionism, Cubism, Pointillism, Art Nouveau, Fauvism, Italian Metaphysical painting), in the understanding that his art would first have to live through a revolution if it was to establish a direct dialogue with the tradition.

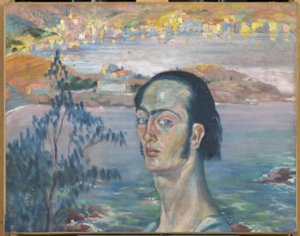

At this early stage in his personal and artistic development Dalí paid close attention to everything that was going on around him and to the influences he was absorbing, always with one eye on the past. His interest in tradition was evident even in his physical appearance. This is already perceived in the twenties, when Dalí begins to paint his first self-portraits. In Self-Portrait with Raphaelesque Neck, probably from 1921[3] [fig. 1], the artist portrays himself in the foreground, with long hair and sideburns. Dalí's words about his appearance in that period show the admiration for Raphael and the Renaissance painters: 'I had let my hair grow as long as a girl's, and looking at myself in the mirror I would often adopt the pose and the melancholy look which so fascinated me in Raphael's self-portrait, and whom I should have liked to resemble as much as possible. I was also waiting impatiently for the down on my face to grow, so that I could shaveand have long side-whiskers. As soon as possible I wanted to make myself "look unusual", to compose a masterpiece with my head [...]"[4]

Dalí was aware of his potential from an early age and was very clear about his goals. He was eager to finish his studies in Figueres and move to Madrid to enrol in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. In 1920, when he was just sixteen years old, he wrote in his diary about the path he intended to take to become an artist after his time at the San Fernando: 'Then I shall win the scholarship to go to Rome for four years; and when I return from Rome I shall be a genius, and the world will admire me. Perhaps I will be despised and misunderstood, but I shall be a genius, a great genius, because I am sure of it[5]. As we can see, Dalí felt that a prerequisite to becoming a genius was to spend some time in Italy, as he was to do so a few years later.

In the nineteen thirties, at a time when he was being acclaimed as an artist of note by the members of the Surrealist group, Dalí felt a renewed interest in Classicism and a rekindled desire to visit Italy. He wanted to follow in the footsteps of his old drawing master in Figueres, Juan Núñez, who had been awarded an engraving scholarship to study at the Real Academia de España in Rome. Dalí sought to emulate the Grand Tour undertaken by so many eighteenth-century intellectuals and artists to refine their taste, as part of their cultural education, and here Gala seems to have had a fundamental role, as the artist made clear in his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí: 'Gala was beginning to interest me in a voyage to Italy. The architecture of the Renaissance, Palladio and Bramante impressed me more and more as being the startling and perfect achievement of the human spirit in the realm of esthetics, and I was beginning to feel the desire to go and see and touch these unique phenomena, these products of materialized intelligence that were concrete, measurable and supremely non-necessary. [...] From day to day Gala was reviving my faith in myself."[6] As he had written a few pages before: 'My surrealist glory was worthless. I must incorporate surrealism in tradition. My imagination must become classic again. I had before me a work to accomplish for which the rest of my life would not suffice. Gala made me believe in this mission. Instead of stagnating in the anecdotic mirage of my success, I had now to begin to fight for a thing that was "important". This important thing was to render the experience of my life "classic", to endow it with a form, a cosmogony, a synthesis, an architecture of eternity."[7]

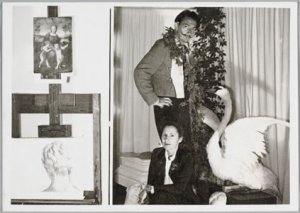

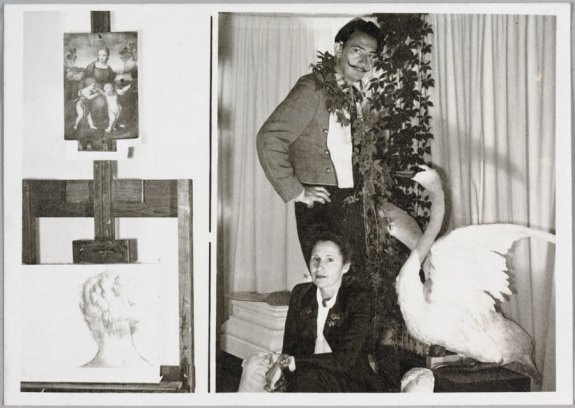

In October 1935, Dalí finally made his first visit to Italy with Gala and the young British poet and patron of the arts Edward James. They travelled from Barcelona to Ravello, near Amalfi, where James was renting Villa Cimbrone. Thrilled with the experience, Dalí enthusiastically recounted it in letters to his friend J. V. Foix, the Catalan poet, journalist and essayist, describing their journey down through Italy by car, a means of transport that allowed them to discover unsuspected delights and all the 'Surrealist corners' unknown to tourists[8]. [fig 2]

After that first trip, Dalí and his wife would make many more visits to Italy, travelling in the next few years to Florence, Lucca, Rome, Sicily, Vicenza and Venice.

Dalí, Renaissance artist

In August 1940, Dalí and Gala disembarked in the United States, where they were to remain for the next eight years without once returning to Europe. For the first few months they were guests of Caresse Crosby at her Hampton Manor estate in Virginia[9], where Dalí made several paintings, which he exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in April 1941. The catalogue of the exhibition included a text entitled 'The Last Scandal of Salvador Dali', in which the artist set out a declaration of intentions and revealed the direction in which his destiny was heading: 'TO BECOME CLASSIC! [...] Now or never!"[10]

A couple of years later Dalí made the following comment on his prolific artistic output since his arrival in the United States: 'America has only developed, to the extent of paroxysm, one of the most characteristic and almost monstrous "secrets" of my personality - my capacity for work"[11]. To this quality we must add Dalí's transformation into a total artist, a process that was consummated at this time. Like the great artists of the Renaissance, here is a creator who refuses to be limited to a single medium or means of expression: Dalí's activity diversified - he was a painter, an illustrator, a writer, a set designer, a scriptwriter, a creator of jewellery... and, in everything he did, he never ceased to be Dalí.diversifica: Dalí és pintor, il·lustrador, escriptor, escenògraf, guionista, creador de joies... I, en tot el que fa, no deixa mai de ser Dalí.

Dalí became a character, a persona who loved to appear in public and make himself the centre of attention. But while he adored being surrounded by glamorous people and leading a very active social life, we should not forget that there was another Dalí, whose great aspiration was to be like the Renaissance artists he so admired. Dalí the painter was aware of the importance of constant, methodical, solitary work: 'I do not go to bed until very late. I don't take very seriously the artist who continually says he has to get "inspired". One must work, work, work. Painters worked very hard in the Renaissance. I can only work when my life is methodic. The maximum inspiration is the maximum of method",[12]. It is worth bearing in mind here that Dalí saw the Renaissance as 'that moment in which the apogee of the means of expression was attained''[13], and this idea is also reflected in his commitment to reviving another Renaissance tradition - that of writing technical treatises on painting.

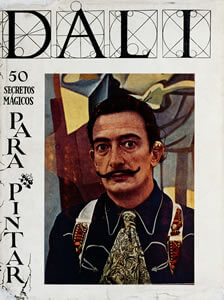

When he came to write his book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship (1948)[14] [fig. 3], Dalí drew inspiration from, among others, Il libro dell'arte by Cennino Cennini. One of the most important early Renaissance treatises on the art of painting, Il libro dell'arte gives information and advice about pigments, brushes, and canvas, board and fresco painting techniques, as well as passing on tricks of the trade. Dalí applied the same approach to his 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship: 'It is a technical and at the same time a philosophical book. In it I analyse and summarize all my ideas, theories, principles and comments on pictorial art.[15] It is a treatise on painting 'for professionals, purely pedagogical.'[16]

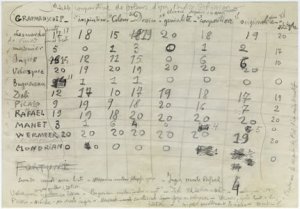

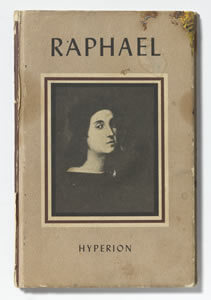

50 Secrets includes a comparative table in which Dalí assigns numerical values to painters ancient and modern for a range of qualities such as technique, inspiration, colour, theme, genius, composition, originality, mystery and authenticity. Inevitably, in this ranking, Raphael receives one of the highest scores. [fig. 4]

Dalí-Raphael, a prolonged revery

“If I look toward the past, beings like Raphael appear to me as true gods."[17]

The young Dalí's passion for Raphael was apparent from an early age. His sister Anna Maria recalled that he would become 'literally ecstatic' when he contemplated the works of the Renaissance artist.[18] davant de les obres de l'artista renaixentista. Els seus amplis coneixements sobre el pintor italià i la seva actitud irreverent durant un examen de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Madrid són motiu, segons Dalí, de la seva expulsió definitiva de l'escola el 1926. Dalí claimed that his extensive knowledge of the Italian painter and his lack of due deference were the cause of his definitive expulsion from the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1926, after he dared to inform the three professors on the board of examiners that they were not fit to assess him because he knew a great deal more about Raphael than all of them combined[19].

Given Dalí's firm belief that painterly technique attained its maximum of experience and perfection in the Renaissance,[20]it was inevitable that he should focus his attention on Raphael, to whom he attributed divine qualities. Dalí felt that he had to interrogate Raphael and 'with fervour turn [his] gaze towards Olympus'[21]. Indeed, in 1941, in the catalogue of his exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery he remarked that his most recent canvases 'seem painted under the complaisant gaze of Raphael'[22], and a few years later he declared that his great desire was to recreate Raphael 'for beauty is one and indivisible'.[23]

A considerable number of Dalí's paintings were inspired by the work of the Renaissance artist.[24] Dalí was interested not only in the themes of Raphael's pictures but also and especially in the drawing, and sought to perfect his own technique by rediscovering the tradition of the old masters: 'that technique, so complete, which permitted them to use, in ultra-limited and contiguous spaces, the coexistence of descriptive varieties [...].'[25]

Gala shared Dalí's fascination with Raphael. In fact it was she, as early as the nineteen thirties, who first turned his attention towards Classicism and Italy: 'We were consumed with admiration over reproductions of Raphael. There one could find everything - everything that we surrealists have invented constituted in Raphael only a tiny fragment of his latent but conscious content of unsuspected, hidden and manifest things.'[26]

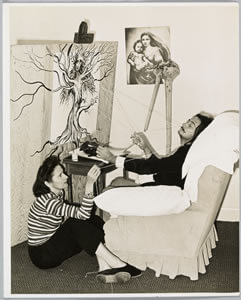

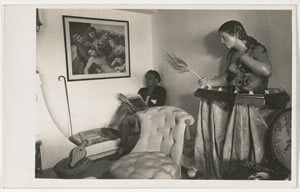

For the most part, Dalí's access to Raphael was by way of reproductions in the many books in his library and prints of individual works[27]. In the photographs that document the different spaces in which he worked we very often see prints, mounted on the easel or directly on the canvas of the work in progress, and framed reproductions can also be seen on the walls of his library and his studios.

The Madonna of the Goldfinch, the Sistine Madonna and The Deposition are the three principal works by Raphael that Dalí kept close to him throughout his life, and in contexts as different as his studio in Monterey and his workshop in Portlligat. [figs. 5-6-7-8-9-10]

It is fascinating to see how Dalí interacted with the books on Raphael in his library, which are now in the Centre for Dalinian Studies. It is as if he were seeking to engage in an unmediated relationship with the works of the Italian master. There are many places where pages are missing, probably removed by the artist for closer study, and others where Dalí has sketched and drawn directly on the pages of the book [figs. 11-12], tracing a grid over the details that most interested him as a first step towards reproducing them on a larger scale in his paintings. One of the most illuminating examples of this for an understanding of Dalí's working process is The Ascension of Saint Cecilia,[28] which was inspired by Raphael's Saint Catherine of Alexandria.[29] Dalí set up a print of the Raphael painting next to his own canvas, and also drew grids directly on the reproduction of the painting in one of his books on the Italian painter's work.

Dalí also made reference to other paintings by Raphael. For his Galarina (1945),[30] inspired by the Ritratto di giovane donna (La Fornarina), Dalí replaced Raphael's model with Gala, 'because Gala is to me what his Fornarina was to Raphael'[31] while Madonna of the Goldfinch served as the basis for works such as Maximum Speed of Raphael's Madonna and Microphysical Madonna (both c. 1954),[32] while the Sistine Madonna was the starting point for paintings such as Antimatter Ear, Cosmic Madonna and The Virgin of Guadalupe, all from 1958.[33]

Raphael continued to be a key reference for Dalí in his later years. The 1979 painting In Search of the Fourth Dimension features details of works by the Renaissance master ,[34]such as the group of figures from the fresco The School of Athens, and drawings by Raphael that Dalí took from his books.[35]

Salvador Dalí, in keeping with his baptismal name, set out to do 'nothing less than to rescue painting from the void of modern art'[36]and he did so by turning his gaze towards Classical artists such as Raphael. According to Dalí, 'modern artists have a horror of the dazzling perfection of the masters of the Renaissance',[37] while he, in contrast, was prepared to swim against the tide and enter into direct dialogue with the great tradition and the painting of Raphael, always with absolute creative freedom. Dalí strove to be classic, Classical, and with his characteristic irony and spirit of provocation he asked: 'who knows if some day I shall not without intending it be considered the Raphael of my period?[38]

-

Salvador Dalí, Diary of a Genius, Doubleday, New York, 1965, p. 84.

-

Exposició S. Dalí, exhibition catalogue, Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona, 1925 (our translation).

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, No. 103.

-

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, Dial Press, New York, 1942, p. 124.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'Un diario: 1919-1920', in Obra completa, vol. I, Textos autobiográficos 1, Destino, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Barcelona, Figueres, Madrid, 2003, p. 118 (our translation).

-

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, op. cit., p. 352.

-

Ibidem, p. 350.

-

Letters from Salvador Dalí to J. V. Foix, from Modena, 4 October 1935, and from Rome, 7 October 1935, in S. Dalí, R. Santos Torroella, Salvador Dalí corresponsal de J. V. Foix, 1932-1936, Mediterrània, Barcelona, 1986, pp. 148-151.

-

Caresse Crosby, who had been married to the poet and publisher Harry Crosby, with whom she had founded the prestigious Black Sun Press, was one of the Zodiac group, whose members regularly bought works by Dalí after 1932, and she accompanied Gala and Dalí on their first trip to the United States in 1934.

-

Salvador Dalí, The Last Scandal of Salvador Dali, exhibition catalogue, Julien Levy Gallery, New York, 1941.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'Dali to the Reader', Galleries of M. Knoedler, New York, 1943.

-

'Dalí, Himself, Is Mystified By His Art (?)', The Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk (Virginia), 14/3/1941.

-

Mostra di quadri disegni ed oreficerie di Salvador Dalí, exhibition catalogue, Sale dell'Aurora Pallavicini, Rome, 1954 (our translation).

-

Salvador Dalí, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, Dial Press, New York, 1948.

-

Armando Rivera, 'Hablando con Salvador Dali', Ecos, New York, 28/12/1947 (our translation).

-

'Dalí visita el museo del Prado', La Tarde, Madrid, 14/12/1948 (our translation).

-

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, op. cit., p. 4.

-

Ana María Dalí, Salvador Dalí visto por su hermana, Juventud, Barcelona, 1949, p. 118 (our translation).

-

Joaquín Soler Serrano, televised interview with Salvador Dalí, A Fondo, RTVE, 1977.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'Dali to the Reader', op. cit.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'What I Mean' [1945], in Obra completa, vol. IV, Ensayos 1, Destino, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Barcelona, Figueres, Madrid, 2005, p. 525 (our translation).

-

Salvador Dalí, The Last Scandal of Salvador Dali, op. cit.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'Appendix. History of Art, Short but Clear', in New Paintings by Salvador Dali, exhibition catalogue, Bignou Gallery, New York, 1947-1948.

-

See the Educational itinerary 'Dalí and Raphael' in the Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'Dali to the Reader', op. cit.

-

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, op. cit., p. 353.

-

See the text 'In Dalí's Studio. On the Working Method of The Ascension of Saint Cecilia' by Irene Civil.

-

See the text Highlighted work: The Ascension of Saint Cecilia by Montse Aguer. Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, No. 706.

-

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, No. 597.

-

Recent paintings by Salvador Dali, Bignou Gallery, New York, 1945.

-

-

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, No. 908.

-

In the case of the painting In Search of the Fourth Dimension we can be sure that the reference was 'A Battle of Nude Warriors with Captives' (Oxford, The Ashmolean Museum, Western Art Drawings Collection, WA1846.179), reproduced in the book by U. Middeldorf, Raphael's Drawings, H. Bitter, New York, 1945.

-

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, op. cit., p. 4.

-

Salvador Dalí, 'The Decadence of Modern Art', Herald American, Syracuse, New York, 20/08/1950.

-

Salvador Dalí, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, op. cit., p. 17.