His contributions to the surrealist movement, through the paranoiac-critical method of interpreting reality, gave rise to a universe of symbols that are now firmly ensconced in the collective imaginary. At certain points in his career, he returned to the great masters of art history, especially from the Renaissance (Raphael, Michelangelo) and the Baroque (Velázquez, Vermeer), even as the diversity of themes found in his paintings, especially those stemming from his interest in science, make him a singular artist, a product of the century he was born in and a key figure in the history of art.

“At the age of six, I wanted to be Napoleon – and I wasn’t.

At the age of fifteen, I wanted to be Dalí and I have been.

At the age of twenty-five, I wanted to become

the most sensational painter in the world and I achieved it.

At thirty-five, I wanted to affirm my life by

success and I attained it.

Now, at fort-five, I want to paint a masterpiece and to

save Modern Art from chaos and laziness. I will succeed! “

Salvador Dalí

This excerpt, from the dedication of 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, one of Dalí’s most important books, which he published in 1948 as a treatise on painting, is a straightforward statement that showcases the artist’s awareness of his own contributions to 20th-century art and painting. Although at that point, Dalí claimed to be a painter within the classical tradition, his painting career began much earlier.

His earliest paintings, which date from between 1910 and 1914, are landscapes of the immediate surroundings of his hometown of Figueres. He would have begun painting them at the tender age of 6. His first contact with the world of art and painting was very likely through the Gowan’s Art Books monographs, which reproduced works by the Old Masters. The volumes on Vermeer, Ingres, De Hooch and Boucher are still preserved in his personal library. One of the first painting movements to have a strong impact on the young painter was impressionism, which he discovered through the work of Ramon Pichot, an artist and member of a family with close ties to the Dalís. Its influence first became evident in 1916 and, until the early 1920s, manifested in still lifes and land and seascapes, mainly of Cadaqués.

Dalí held his first public exhibition of his paintings in 1919, at the Societat de Concerts (Concert Society) at the former Figueres Municipal Theatre, today the Dalí Theatre-Museum. Contemporaneous critics reported on the young artist’s show: ‘It is strong work, done with vivid colours, broad, vibrant drawing, and intense feeling, which surprises by reducing values to their maximum simplicity.’ He began to paint his first self-portraits around 1920. In 1922, he started at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts) in Madrid, where he received his specialized training, after his drawing classes with the teacher Juan Nuñez in Figueres. In this period, Dalí admired and emulated nearly all the ‘-isms’ of avant-garde painting — cubism, dadaism, fauvism, purism and vibrationism — as well as Italian metaphysical painting. His greatest early references included cubism and Pablo Picasso, whom he met personally during his first trip to Paris in 1926.

After this training period, around 1927, he began to experiment with his own pictorial language. It is at this point that he began to put forward his own surrealist aesthetic, developing a highly peculiar iconography characterized by dismembered bodies and decaying elements, in paintings such as Aparell i mà (Apparatus and Hand) (P 195) and La mel és més dolça que la sang (Honey Is Sweeter Than Blood) (P 194). He laid out the theoretical foundations for these paintings in his article ‘Sant Sebastià’ (Saint Sebastian). In this period, Dalí also incorporated the mixed-media technique in a series of oil paintings, which, at one point in 1928, verged on abstraction.

One of Dalí’s greatest contributions to the history of painting was his work in the context of surrealism. In 1929, he joined the surrealist group in Paris. This was also the year that he met Gala in Cadaqués. It was a true turning point for the artist. Thereafter, he focused on cultivating his more personal style and honing his paranoiac-critical method, which he presented in four essays published in La femme visible (The Visible Woman) in 1930. Paintings such as La mémoire de la femme-enfant (The Memory of the Woman-Child) from 1929 (P 236), La persistance de la mémoire (The Persistence of Memory) from 1931 (P 265) or Le spectre du Sex-Appeal (The Spectre of Sex-Appeal) fromc. 1934 (P 338) are some of his masterpieces from this period. Also of note are his double images, through which he connected with his explorations of the conscious and unconscious, reality and imagination. Around 1938, he allowed the vibrant palette of surrealism to languish, and his paintings began to feature inhospitable landscapes with new symbolic elements denoting a concern for the European political and social situation. Paintings such as Imperial Violets (P 474) or Endless Enigma (P 464) bear witness to his unease and discouragement in the run-up to World War II.

With the outbreak of the global conflict in Europe, Dalí and Gala departed for the United States, where they arrived in August 1940. There, the artist embarked on a new phase, in which he sought to excel and vindicate himself as a classical artist. And he succeeded, especially through his painting. In the catalogue for the 1941 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, Dalí emerged as a champion of the Renaissance and the restoration of the golden ratio. On more than one occasion, the artist acknowledged Gala’s decisive influence in this conversion. This change of course manifested itself gradually in his painting, making it impossible to pinpoint an explicit renunciation of surrealism. He began by introducing timid evocations of classical culture, such as knights, marsupial centaurs, or classical architecture. Beginning in 1945, with paintings such as Galarina (P 597) or My Wife, Nude, Contemplating Her Own Flesh Becoming Stairs, Three Vertebrae of a Column, Sky and Architecture (P 598), his painting irrefutably became a call for a return to classical tradition. This transformation culminated around 1948 with his acclaimed Leda Atomica (P 642) and the publication of his treatise on painting, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship. In its pages, he named Vermeer, Raphael, Leonardo, Velázquez and Picasso as the painters he most admired, and, indeed, their influence is the most noticeable in his work. At a time when abstract expressionism commanded the spotlight on the American and European stages, Dalí sought to become the ‘saviour’ (as the name ‘Salvador’ implies in Spanish and Catalan) of modern painting and, thus, to pick up the mantle of classical tradition and oil painting in the vein of Van Eyck and Vermeer. In this period, he also painted portraits for American high society.

Assured of his success, in the 1950s, Dalí took his painting in a new direction, influenced by classicism, science and nuclear physics, inaugurating his nuclear mysticism period. In his Mystical Manifesto, published in 1951, he explained the emergence of religious themes in his work, his renewed interest in the Italian Renaissance and his desire to become classical by incorporating the scientific knowledge of the time. He gradually began to incorporate religious elements, such as the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child or the Crucifixion, into masterpieces such as The Madonna of Portlligat (first version) from 1949 (P 643) and Le Christ (The Christ) from 1951 (P 667). His interest in atomic structure, disintegration and the discontinuity of matter found especially fruitful outlets in works such as Gala Placidia (P 672)from 1952.

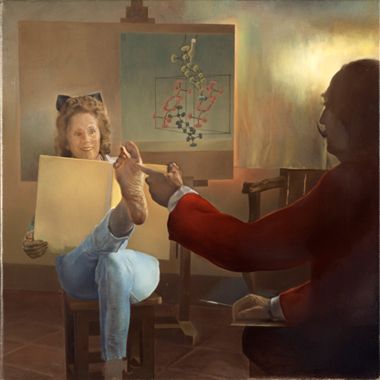

His paintings from the 1960s and 1970s evidence a wide variety of influences and concerns. His renewed embrace of some of his key contributions to surrealism is apparent in the prominent role of double images in Double Image with Horses, Numbers and Nails from c. 1960 (P 763) and The Hallucinogenic Toreador from 1970 (P 822). He was likewise influenced by certain American art movements, such as Pop Art, his commitment to science, especially everything having to do with the structure of DNA, and three-dimensional optical phenomena. Dalí associated this quest with immortality, with his desire to transcend. His studies on stereoscopy (a technique for producing a relief effect by means of a device that combines two flat images of the same object taken from slightly different viewpoints to create an illusion of depth) and anaglyphs (a system consisting of the superimposition of two images in complementary colours) resulted in several paintings, such as the stereoscopic pairs Dalí Seen from the Back Painting Gala from the Back Eternalized by Six Virtual Corneas Provisionally Reflected by Six Real Mirrors. Stereoscopic work, 1972-73 (P 853) or El pie de Gala. Obra estereoscópica (Gala’s Foot. Stereoscopic work), c. 1974 (P 1104), and Untitled. Pietà. Work to be viewed with anaglyphs, 1975-76 (P 1041).

Dalí stopped painting in 1983. In his final works, from the early 1980s, he evoked, on the one hand, some of the painters he had always admired, especially Michelangelo and Velázquez. Works such as Untitled. Giuliano de’ Medici after the Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici by Michelangelo (P 980)or Untitled. After ‘The Infanta Margarita of Austria’ by Velázquez in the Courtyard of El Escorial (P 954), both from around 1982, are among the main testaments to this. On the other, and without losing sight of his scientific curiosity, through works such as El rapte topològic d’Europa. Homenatge a René Thom (Topological Abduction of Europe. Homage to René Thom) (P 1009) or Swallow’s Tail and Cellos. The Catastrophes Series (P 1013), both painted in 1983, he integrated the theories of the mathematician René Thom. In this final period, Dalí re-embraced his bedrock references without ever ceasing to allude to Gala, who died in June 1982.